Taped to the top of my computer monitor is a note that

reads, “If you’ve met one person with autism, you’ve met one person with

autism.”

Within the spectrum of autism

there are many diverse characteristics, and for an individual how those

characteristics are displayed can change on a daily basis.

Back in the fall I had the opportunity to

hear

Paula Kluth

speak as the keynote speaker at

OCALICON.

She described providing interventions, to

students with autism, as playing the

Race Game on The Price is

Right.

One morning I may come

in and pull the handle and have four correct interventions.

The next morning I’m going to come in,

pulling what I think is the same lever, and I’m only going to have one or two,

maybe even zero, correct interventions in place.

The ever changing results, to pulling the lever, are

something I have experienced, in many facets this year, but particularly in the

area of writing. A particular student

was able to write creative stories with no issues last year. However, getting him to write this year has

been a challenge, and the more interventions I try the more he seems to be

resisting. I know the ideas are in his

head, but he is stuck in inertia and I have struggled to help him find a way

out, or to break the inertia. I have

used a plethora of ideas: picture

prompts, sentence starters, scribing his words, word prediction software,

having him type on the computer, graphic organizers, hand over hand initiation,

etc. However, this leads to immediate

tears and refusal to complete the assignment.

Today I finally had a chance to read

I

Hate to Write by Cheryl Boucher and Kathy Oehler, and I’m kicking

myself for not reading it sooner!!!

They

describe the writing process as needing the four areas of the brain; language, organization,

motor skills and sensory processing, to work together to accomplish the task of

writing.

However, the brain of a person

with ASD appears to send far fewer of these coordinating neural messages (Boucher

and Oehler, 2013).

Therefore, writing

becomes an inefficient and very frustrating process.

This amazing book provides teachers with common

concerns around writing, why students with ASD may react in a certain way (with

research to back it up), teaching strategies and “Take It and Use It”

pages.

Within every area of concern, the authors

provide suggestions in how to address all four areas of the brain, involved in

writing, in order to make writing a happy and successful process.

Quickly, I have realized that I was providing interventions

for the student during the process of brainstorming and writing, but I was

completely ignoring his environment before writing. This afternoon I met with the student and had

him do hand exercises, seat push-ups and deep breaths (ideas provided in the

book). I then had him pick a big muscle

warm up (list provided in the book), and complete that activity for 5-10 minutes. This student decided to jump on the

mini-trampoline (only if I would count how many times he jumped, of course).

After he completed these activities I started to talk to him

about writing, and how that process feels for him. Just

at the mention of writing I thought for sure he was heading into a

meltdown. He refused to talk about writing, just the

same as he refused to write. I know he

has the ideas in his head, but they are stuck up there. I immediately pictured a strainer that is

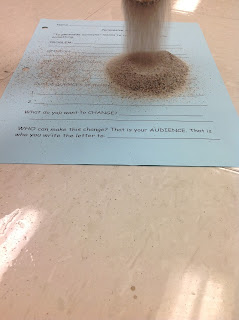

clogged, so it won’t let anything through the holes. Wouldn’t you know it, I happened to have a

strainer in my classroom. I asked the

student if he wanted to play with some rice, and a meltdown was prevented. While he was playing with the rice, I filled

my strainer full of it, and held it over top of his persuasive writing planning

sheet. I asked him if the strainer was

full of rice (ideas).

He looked at me like I was a crazy lady and started

laughing, because it was obviously full.

I told him that when I look at him, I know his brain is full of ideas

(rice). However, no matter how hard I

shook the strainer with rice; only one or two pieces would escape. Just like, no matter how much he thinks about

his ideas, he can’t seem to get them into words.

I then filled the strainer with sand, and all of it quickly

fell onto the planning sheet.

I explained to him that I wasn’t able to change rice into

sand, but I could plan what I put into the strainer to make it fall out onto

the planning sheet. His goal was to be

able to start writing with sand, and not rice, as his ideas. Doing his hand exercises, big muscles

exercises and chewing gum are his strategies to use to turn rice into

sand.

Using this analogy, I’m hoping, is helping this student not

feel at fault or “lazy”, in terms of why he is stuck in inertia. It’s not that he is refusing to work, resisting

the assignment, doesn’t have great ideas or doesn’t have the ability to

write. I believe that when teachers, me included, say

to him to let us know if he doesn’t understand, than he feels guilty for not

understanding. In reality, he does

understand, but he can’t seem to get the rice through the strainer. I have encouraged him to let his teacher and I

know if he needs help turning sand into rice.

This conversation, and experience, has probably been the most excited I

have ever seen this student about writing.

He was talking to me about his persuasive writing idea the entire way

back to the classroom. I believe the

activities prior to our rice/sand conversation helped the sensory part of his

brain communicate with the language portion of his brain.